- Home

- Amy Sarig King

The Year We Fell From Space Page 12

The Year We Fell From Space Read online

Page 12

“Yeah. Like a bank robber. That’s what I was saying,” she says.

“It’ll all be over by tomorrow,” I say. “For now, do you want some hot chocolate?”

“It’s hot outside.”

“Lemonade?” I wipe my palms on my shorts.

“I don’t need anything,” Jilly says. “It’s almost bedtime. Probably not a good idea for me to drink something. I’ll have to pee.”

“I have to take a shower,” I say. “I’ll be back to read to you when I’m out.”

“Where’s Mom?” she asks.

“She went for a walk.”

“She’s mad about Tiffany.”

“It’s okay,” I say. “It will all work out. Promise.”

Jilly looks at me like I’m weird. I guess I am weird. I made a deal with the stars and that’s probably weird. When I’m getting dressed after my shower, I look at the meteorite—proof that the stars always tell the truth.

Jilly hands me the one book she knows I hate and I read it to her for bedtime like I promised. It’s long and even though Jilly falls asleep near the end, I read the whole thing. I turn off her light, close her door, and go to my room.

I find the one tiny meteorite that fell and roll it between my finger and thumb.

“It’s going to be our good luck charm,” I say to the rock.

“Okay.”

“I’m going to keep it in my pocket until this whole mess is over,” I say.

I hear the back door close and Mom come in.

“Must be nice to be a meteorite,” I say. “You’re probably really old and people respect you and stuff.”

“You should go and talk to her,” the rock says.

“She’s probably working late.”

“If you stay up here, she won’t know that you want to talk to her. But if you go down and tell her, she’ll know.”

I ask, “What did it feel like to fall from space?”

“Scary,” the rock says. “And hot.”

That’s how I feel when I walk down the stairs to talk to Mom.

She’s not working late. She’s reading a book. This makes me feel even worse because she doesn’t get a lot of time to read books.

“It’s past ten,” she says.

“You okay?” I ask.

“Yeah. Thanks. I’m so sorry I got upset after dinner. I just—it’s hard still, sometimes.”

I try a few sentences in my head about Tiffany but none of them sound right. It’s like the only person I can really talk to around here is the meteorite. I manage, “You always say it’s adult-stuff—like we don’t know what’s going on. But I think I know a lot more than you think I do.”

Mom smiles and shakes her head in a way like she knows what I’m talking about.

“I thought you guys had the perfect marriage,” I say.

“We did, once. Things change,” Mom says.

“I don’t understand why Dad changed so much. What happened to him?” I ask.

“Your dad has a lot of guilt, you know. Guilt he can’t let go of or can’t get ahold of. It kinda ate him up,” she says.

I say, “He’s such a mess now. It’s all fake or something. Like when he took us to that baseball game on the first day we saw him. He ate a hot dog!” I say.

“He struggles a lot,” Mom says. “With things that you and I can’t understand. It’s different for guys I think. I don’t know why it’s different for them, or if it really is, but I guess it’s that whole knight-in-shining-armor thing they have. They think they have to be perfect to save the day. They don’t like mistakes. I don’t know if it’s only boys. But my dad has it. My brother has it. Your dad has it.”

“But nobody’s perfect,” I say.

“Exactly.”

“So why be a jerk, then?” I ask. “Why be a jerk instead of perfect? Why not just figure out that nobody is perfect and not be a jerk?”

Mom sits for a while and bites the inside of her mouth. She finally says, “Guilt is probably the most powerful feeling in the world. It really makes a mess of people.”

“But if someone is guilty, they should make things right and not do whatever made them guilty again. Like—remember that time I said my room was clean but really I stuffed everything in my closet? Dad told me that lying leads to guilt and he was right! I stopped lying and I felt better,” I say.

“Maybe kid guilt and grown-up guilt are different,” she says. “I don’t know. I’m not him. I do know the minute he let that guilt get a grip on him, he made a lot of decisions without talking to any of us first.”

“Like moving Tiffany in and not telling us.”

She shakes her head in disappointment. “I just wish he would have told me so I could have prepared you. It must have been weird,” she says.

“It was.”

“I’m sorry he did that to you,” she says.

“I’m sorry he did that to you, too,” I say. “All of it.”

We hug. I go to bed and think about guilt and mistakes and perfection.

The whole reason I had to kick Ethan McGarret in the privates in fourth grade was because I kicked a home run in kickball at recess and his team lost. His team was undefeated until that day.

So he chased me around the field and up the steps and around the sidewalks until I realized that he wasn’t going to stop. Until I realized he was actually angry. At me. For kicking a ball. For getting a home run. At recess.

I ran out of breath and hid where the doors to school were. He found me and put his hand on my shoulder— grabbed it hard. His other arm pulled back to punch me and I looked at his face. I kept saying his name before I kicked him. “Ethan! Ethan!” But he was somewhere else.

Now I know the name of that place.

Planet Perfection.

Where every kickball game is won, every answer in class is right, and every person at school wants to be your friend because you’re cool.

Planet Perfection doesn’t exist.

I don’t really feel guilty about misplacing Leah’s mom’s ring. I know it was wrong. But I had no other choice. The ring was lying there on the floor of the hallway. I could have just given it to Leah, but because she excommunicated me the day before, she would have thought I stole it. I could have given it to a teacher, but I thought I’d get in trouble. So I put it in my pocket until we went to the library a half hour later and I found a place where it would be safe.

Sounds hard to believe. Which is why I never gave the ring back. But now I have to give the ring back. My family depends on it. And I never want to get so guilty that I end up like Dad.

I can’t stop thinking about Jilly getting caught. She’s so young. I should have never sent her on this mission. I can’t even eat my lunch I’m so nervous. My new friend Maya asks if I’m okay. I tell her it’s the rain—that it makes me weird. She says that I should never move to Seattle because her dad lived there for a while and he said all it did was rain.

“You’re so nice,” I say.

“So are you,” she answers. But I know I’m not nice. I’m a horrible sister. I touch the little meteorite inside my pocket to make me feel better about it, but it doesn’t.

By the time the bus drops me off at the end of our lane, the rain is coming down sideways. Mom is waiting in her car at the bus stop.

“Finn!” she calls out the window. He looks around. “Finn! Let me drive you home!”

Finn gets into the back seat and he’s soaked. Mom takes off after the bus and Finn says, “Thanks, Mrs. J.”

“How you doing?” Mom asks.

“Okay, I guess.” He pushes his wet hair out of his face, but it falls back again.

“How’s middle school?” she asks.

“I’m getting used to it,” he says.

“Liberty is finally getting used to the schedule. She was so tired at first, weren’t you, Lib?”

I’m so nervous, I can’t find one word to say to Finn Nolan. All I’m thinking about is Jilly sitting in the chair in front of Ms. S.’s desk, having to

explain how I sent her on a mission. She’s never been in trouble, not once.

The road is like a shallow river. Mom drives up the hill, turns into the Nolans’ driveway, and parks by the front door.

“Thanks again!” Finn says. He seems a lot nicer when Mom is around. I’m probably worrying about him for nothing.

“I’ll get Patrick when I pick up Jilly,” Mom says. “Go get dry!”

As we drive back to Lou’s lane and wait for Jilly’s bus to come, I get so nervous about the mission that I feel tingly all over.

“He’s a nice kid,” Mom says.

“I guess.”

“You didn’t say anything to him,” she says.

“He doesn’t really talk to me,” I say. “Middle school is awkward.”

“I hope they’re doing okay,” she says. “I worry about those boys.”

A tree limb falls onto the road in front of us. We both jump.

Mom gets out of the car, drags the limb to the side of the road, and gets back in, soaked.

Thunder roars.

Jilly’s bus comes around the corner and stops. Jilly runs to the car and Mom beeps the horn at Patrick, but he doesn’t even look our way. She rolls down the window and yells. As Jilly gets into the car, I give her a look like she shouldn’t say anything.

Patrick gets into the car then and thanks Mom for the ride home.

Once we drop Patrick off at his house, Jilly says, “We had an assembly today about instruments. I think I want to play the tuba.”

It takes all the willpower I have not to ask how library class was. I say, “Tubas are cool.” I feel stupid for saying it. But tubas are cool.

By the time we get back to our house, all of us are soaked and cold and Jilly is crying because the thunder is so loud.

And then the power goes out.

Mom lights candles and pulls out two camping lanterns. We stay together, so I can’t ask Jilly about the mission. While we’re eating, she must remember it.

She says, “So, because of the assembly, we didn’t have any special classes today. Library got moved to Wednesday.”

She looks right at me when she says it. Something about her looks so small and innocent, I start to cry. I can’t stop myself. And when she sees me cry, she starts, too. The thunder is so loud, it shakes the house. The rain is so heavy, Mom checks to make sure the basement isn’t flooding.

I whisper, “Don’t worry about the mission anymore, okay?”

“It’s fine. I just have to wait ’til Wednesday.”

“I don’t want to get you in trouble,” I say.

“I won’t get in trouble,” she says.

Lightning touches down in the backyard and lights up the dark house. Thunder rattles the windows. We go to bed early, and all three of us land in Mom’s bed because the storm is so scary we can’t sleep.

Jilly told me this morning that she’s confident that today she will find the item. Part of me wanted to talk her out of it, but part of me really wants to get this over with. I told her she was awesome for doing it. I am still the worst sister ever.

I thought about talking to Mom about it. I thought about making an anonymous email address and sending a letter to Ms. S. so she could go get it herself. I had a bunch of ideas like this. All of them make me a coward.

But now that today is here, I’d rather be a coward than a bad sister.

I don’t pay attention to anything in school. Maya says I’m weird at lunch again and I probably am. I don’t take any notes in biology class. I keep watching the clocks and the closer it gets to dismissal time, the slower the clocks move.

I see Finn Nolan on the bus. He’s still quiet. His face is always scrunched up into itself under his uncut bangs. I think maybe he’s being his own middle school bodyguard, like the way Dad had Bobby Heffner. I say hi, but he doesn’t answer me so I sit in my seat and look out the window. The bus ride is four million hours long.

When I get home, Mom has a tent set up in the living room. She’s inside the tent, sleeping.

I say, “Hi, Mom.” She shifts a little and stays asleep. I go upstairs to my room.

“I’m the worst sister ever,” I say to the rock.

“I can’t disagree,” the rock answers.

“She wanted to do it,” I say.

“Sure.”

“I’m awful,” I say.

“Probably not awful,” the rock says. “But you could have done it yourself.”

“I know.”

I go back downstairs and I wait for Jilly. The clock comes to a standstill. I decide to meet her at the bus stop and I leave a note for Mom if she wakes up while I’m gone.

The frogs are loud and it’s funny how I don’t hear them when I’m not listening. Birds, too. Jilly says she wants to live in the city one day. On days like this, I can’t see myself living anywhere but the country.

Jilly gets off the bus and sees me. As she crosses the road in front of the bus, the first thing she does is give me the thumbs-up. Both hands. Points to her pocket. Then she goes back to pretending like today is any other day. I squeeze the pocket-meteor between my fingers. It feels lucky.

“Where’s Mom?”

“Taking a nap,” I say. “How did it go?”

“Mission accomplished. We will never speak of it again,” she says, and she hands me the ring.

I look down at it in my palm and feel a mix of shame, regret, excitement, and relief. I stop and hug her and pick her up and spin her around. “Thank you!” I say.

“I don’t know what you’re thanking me for,” she says.

“Were you scared?” I ask.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about.” She really meant it when she said we wouldn’t speak of it again, I guess.

Mom’s awake when we get home and she asks Jilly and me to lie down in the tent that’s still in the living room. I keep my hand on the pocket where the ring is. I’m afraid it will fall out. I’m afraid Mom will see it.

I finally crawl out of the tent, which Mom deems too small for two real people, and I go to my room.

“I got it back,” I say to the rock.

The rock says, “Good for you, I guess.”

“Everything is fine. Jilly didn’t get caught.”

The rock says, “If you think everything is fine, it must be fine.”

“I need help. I need to figure out what to do next,” I say.

The rock says, “Tell Mom. Go to Leah’s house tonight and give it back.”

“I was thinking I could drop it in Mike’s backpack. Or Finn’s! I don’t know. It could get them in trouble.”

The rock says, “Tell Mom. Go to Leah’s house tonight and give it back.”

“I could put it in the lost and found at school, but then it could get stolen and I don’t want it to get stolen. I could get someone else to leave it in the office. Or I could get them to give it to a teacher and say they found it somewhere.”

The rock says, “Tell Mom. Go to Leah’s house tonight and give it back.”

“You’re no help at all,” I say.

The rock says, “If you say so.”

I put the ring into an envelope. I print out Leah’s name on the printer. I tape the name to the envelope. I put the envelope into my backpack front pocket. I take out my Spanish homework and sit at the table.

I feel like calling Dad and asking him if he’s ready to come back now.

When I go to bed, I cover the meteorite with a blanket so it doesn’t see me.

I know that’s irrational, but what’s rational when I’m making deals with things that are hundreds and thousands of light-years away?

I take the item to school on Thursday morning and slip it into the anti-bullying box outside the guidance office before homeroom. I stand across the hall for a minute to make sure no one saw me, and then I go to my locker.

By biology class, I hear that Leah got her ring back.

That’s it.

The whole thing is over.

I expected to feel a

huge weight lift, but I don’t. I try to imagine life with Dad back at home. I have trouble imagining it because all I can remember are the bad times. I try to picture the family of deer. Holding his hand.

The weight still doesn’t lift.

The weekend is relaxing. Jilly and I sleep past ten on Saturday. Mom got a few new movies on DVD and we hang around in our pajamas and eat popcorn and watch them. We make pizza Sunday night and have a picnic on the living room floor.

Monday, I have my hopes up for a phone call from Dad. I don’t know why. The stars had all weekend to fix things. Leah has her dumb ring back. Dad doesn’t call.

Tuesday, I forget all about Dad until he calls during dinner and he and Mom have a talk about something in code. I hope the code is that they love each other again and he’s moving back in.

On Wednesday, we have another storm like last week. Lou comes to the house to double-check if the basement is dry and to give Mom some meat. Sounds weird, but Lou doesn’t just hang the heads on his wall when he hunts. He makes food, too.

“Elk!” Mom says, digging through a cooler that’s in the bed of Lou’s truck. “I love elk!”

Jilly makes a face like she’d never eat elk in her life.

“You eat elk, Jilly. You just don’t know it,” Mom says.

Lou leaves some kind of pump in the basement just in case. “It’s gonna be windy with lightning. If you lose power, call me. I have the generator ready.”

Lou clearly doesn’t understand Mom at all. She could live without electricity indefinitely. She likes it that way. “Bring on the zombie apocalypse!” she says, flexing her arms. Lou laughs and gets back in his truck.

The storm is worse than last week’s. It’s a leftover hurricane. The lightning is scary and the thunder is loud. Jilly and I sleep in Mom’s bed again.

We never really recover from Wednesday. I’m tired and Jilly is cranky. Or maybe Jilly is tired and I’m cranky. I can’t shift my mood. I know why, but I don’t say why because it’s a stupid reason why. Thursday I try to daydream Tiffany moving out of Dad’s new house. I see them argue and I see her packing her WELL-BEHAVED WOMEN RARELY MAKE HISTORY mug into the trunk of her car. I see Dad sitting in his darkened bedroom, lonely and ready to finally just come home. By the time I get back from school, I expect to see him there.

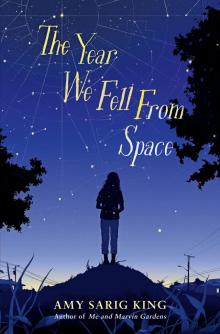

The Year We Fell From Space

The Year We Fell From Space